Ancient Shipwrecks Rewrite 500 Years of Iron Age Trade!

Archaeologists from the University of California, San Diego, and the University of Haifa have uncovered something remarkable off Israel’s Carmel Coast: the oldest known Iron Age ship cargoes ever found in a known port city. Their discovery, published in Antiquity, offers rare, direct evidence of maritime trade in the eastern Mediterranean and reshapes what we know about the movement of goods and power during this period.

The discoveries were made in the Dor Lagoon (also known as Tantura Lagoon), once the bustling harbour of the ancient city of Dor. The international research team, led by Professor Thomas E. Levy (UC San Diego) and Professor Assaf Yasur-Landau (University of Haifa), found three separate underwater cargo assemblages dating from the 11th to the 6th centuries BCE.

These finds represent the earliest direct connection between maritime trade and an Iron Age city in the southern Levant, a link that until now had only been suggested by land-based evidence.

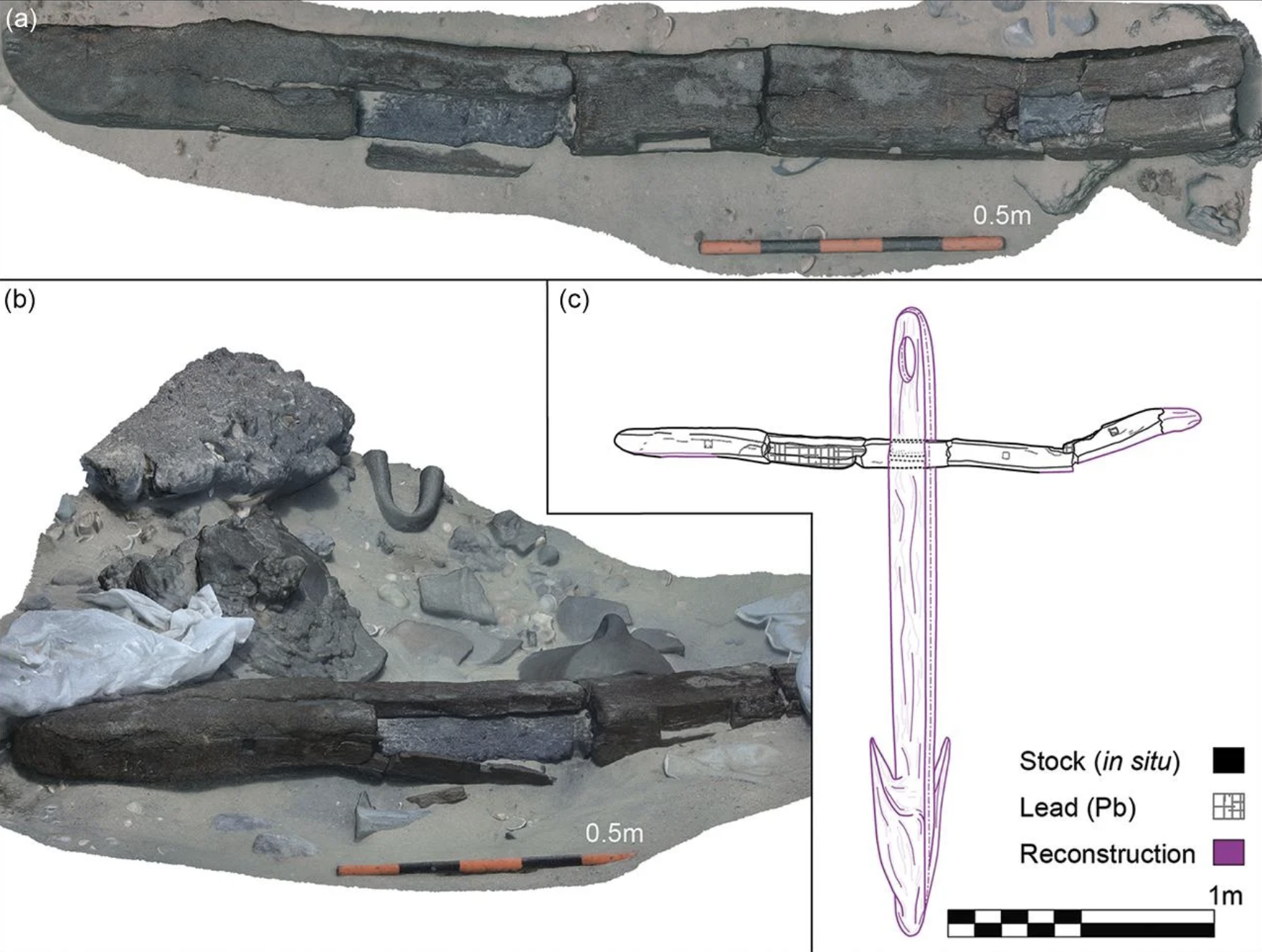

The oldest assemblage, known as Dor M, dates to around the 11th century BCE. It includes storage jars and a ship’s anchor inscribed with Cypro-Minoan symbols, evidence of contact between Dor, Cyprus, Egypt, and the Phoenician coast.

This discovery fits neatly with the Report of Wenamun, an Egyptian literary text from the same era describing voyages to Dor and nearby ports. Together, they highlight Dor’s importance in the early networks of trade that emerged after the collapse of the Late Bronze Age.

The second assemblage, Dor L1, dates to the late 9th or early 8th century BCE. It contains Phoenician-style jars and delicate bowls, but unlike the earlier cargo, it shows no trace of Egyptian or Cypriot imports.

Archaeological evidence suggests this was a time when regional trade slowed and Dor’s influence waned. Yet the very presence of these goods at sea shows that maritime commerce continued, even in an era of political and economic isolation.

The final and best-preserved cargo, Dor L2, comes from the late 7th or early 6th century BCE, a time when Dor was under Assyrian or Babylonian rule. Among the finds were Cypriot-style amphorae, iron blooms (semi-processed lumps of iron from smelting), and traces of resin and grape seeds inside the jars.

These materials point to industrial-scale metal trading and the exchange of goods such as wine and dates. The radiocarbon dating aligns Dor’s activity with a broader network that linked the eastern Mediterranean’s great powers, from Anatolia to Phoenicia.

The excavation combines traditional underwater archaeology with advanced “cyber-archaeology” techniques, including 3D modelling, multispectral imaging, and digital mapping. This high-tech approach, developed through collaboration between UC San Diego’s Qualcomm Institute and the University of Haifa, allows researchers to reconstruct submerged trading routes and harbour structures with remarkable accuracy.

So far, just a quarter of the Dor sandbar has been excavated. Archaeologists believe further digs could reveal more artefacts, possibly even fragments of ship hulls. But even at this stage, the discoveries make it clear that Dor was a thriving maritime hub whose fortunes rose and fell alongside the great empires of the Iron Age.

Spanning half a millennium of history, these cargoes show that while kingdoms and rulers came and went, the Mediterranean Sea remained a constant conduit for trade, ideas, and cultural exchange. The ships that sailed into Dor carried more than just goods, they carried the enduring story of human connection across the ancient world.