11,500-Year-Old Tools Found on Skye Reveal Scotland’s Earliest Human Settlements!

Archaeologists have made a remarkable discovery on the Isle of Skye—ancient stone tools dating back around 11,500 years, offering compelling new evidence of some of Scotland’s earliest known human activity. This find not only pushes the timeline of human presence in the region further back than previously thought, but also reveals that people had ventured much further north during the Late Upper Palaeolithic (LUP) than we ever imagined.

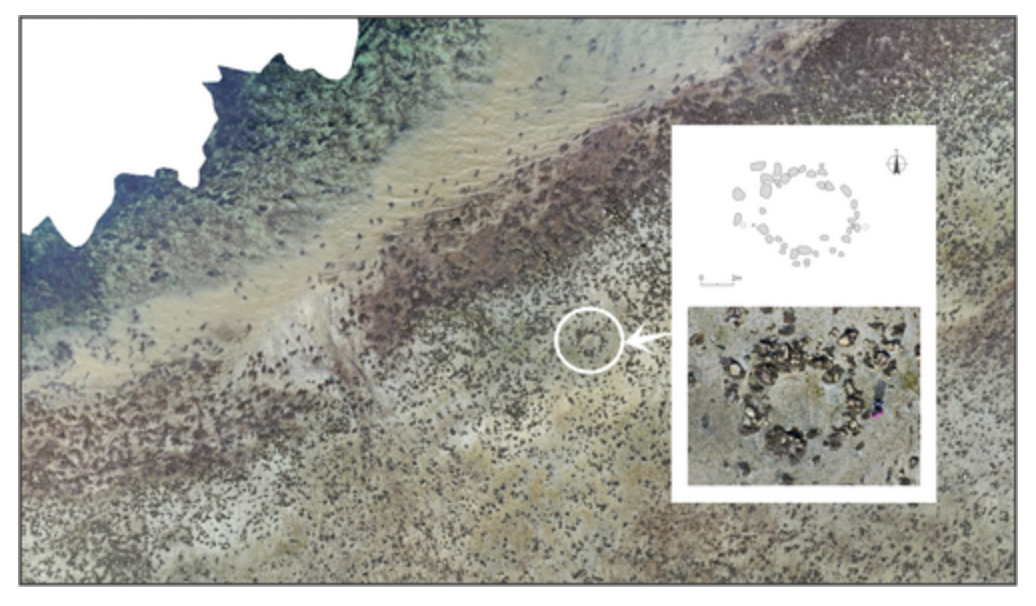

Led by Professor Karen Hardy from the University of Glasgow, alongside the late local archaeologist Martin Wildgoose, the project uncovered what is now the most substantial concentration of early human evidence along Scotland’s west coast. Their findings were recently published in the Journal of Quaternary Science, under the title At the far end of everything: A likely Ahrensburgian presence in the far north of the Isle of Skye, Scotland.

In collaboration with researchers from the Universities of Leeds, Sheffield, Leeds Beckett, and Flinders University in Australia, the team also reconstructed the ancient landscape and sea levels to better understand the environment these early inhabitants would have encountered.

At the time, Scotland was emerging from the last Ice Age—specifically the Younger Dryas (also known as the Loch Lomond Stadial)—and was still largely glaciated. The people who made their way here were likely part of the Ahrensburgian culture of northern Europe. These nomadic hunter-gatherers are believed to have crossed what is now the North Sea—then a land bridge known as Doggerland—to reach Britain, eventually making their way as far as Skye.

Professor Hardy described their migration as “the ultimate adventure story.” These early humans likely followed herds of animals as they travelled into newly habitable lands, witnessing dramatic changes in the landscape as the ice retreated and the Earth slowly rebounded. She highlighted Glen Roy’s “Parallel Roads” as an example of the geological transformations these people would have seen with their own eyes.

When they finally arrived on Skye, they made clever use of the natural resources around them—crafting tools from locally available stone, settling near rivers and coastal areas, and valuing materials such as ochre, which held cultural and possibly spiritual significance in ancient times.

While hard evidence is still limited—often found by chance rather than design—Skye joins a growing list of sites across Scotland (including Tiree, Orkney, and Islay) where traces of the Ahrensburgian culture have been uncovered. These discoveries suggest a broader, more established human presence than previously thought. Although much of the original landscape is now lost beneath the sea or altered by time, places like Sconser hint at a very different past—when lower sea levels once connected islands such as Raasay to Skye, making them ideal places for early humans to explore and settle.

This discovery on Skye not only enriches our understanding of Scotland’s distant past but also reminds us of the incredible resilience and ingenuity of our earliest ancestors.