A Rare Terracotta Head Unearthed at Magna Roman Fort Near Hadrian’s Wall!

Archaeologists working at Magna Roman Fort, close to Hadrian’s Wall, have uncovered a small but intriguing terracotta head dating to the third century CE. The piece came from soil used to fill a defensive ditch along the fort’s northern edge. It was discovered on 5 June 2025 by volunteers Rinske de Kok and Hilda Gribbin during a community dig forming part of a five-year research project funded by The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

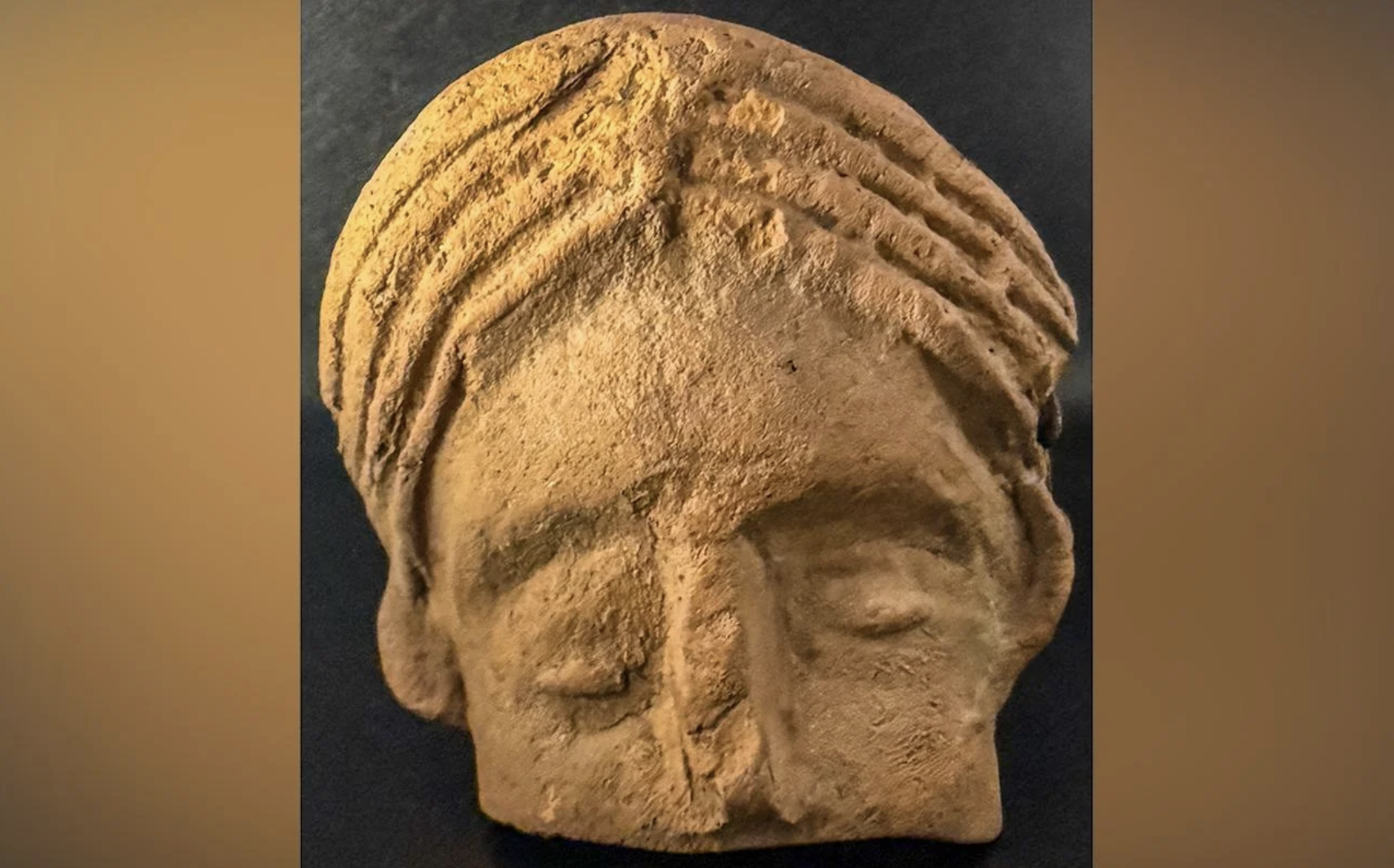

The head measures just 78mm high and 67mm wide. Made from orange clay, it depicts a woman with a centre-parted hairstyle and four plaited strands falling down each side of her face. Unfortunately, the section below the nose has broken away, so the mouth and chin are missing.

At first glance, the craftsmanship appears rather uneven. The eyes sit at slightly different levels, the ears are only roughly shaped, and the surface is more hastily finished than carefully smoothed. According to a Roman finds specialist who examined it, the head was likely made by a learner rather than a skilled craftworker. The asymmetry and quick modelling suggest it may have been practice work, produced locally rather than imported. After all, it would hardly have been worth transporting over any distance.

Free-standing terracotta heads are exceptionally rare in Roman Britain. Face pots, vessels decorated with facial features, are far more common on both military and civilian sites. What makes this discovery even more fascinating is that Magna has produced a similar head before.

In the nineteenth century, a more refined terracotta head and bust were found at the same fort. Records show that this earlier piece was donated to the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne in 1982. Today, it remains in storage at the Great North Museum Hancock.

When the two heads are placed side by side, the similarities are striking. The hairstyle, facial shape and overall proportions closely match. Archaeologists involved in the current excavation believe both pieces may represent the same individual. One theory suggests that an imported original could have served as a model, with a local craftworker attempting to copy it in clay. This would neatly explain the lower quality of the newly discovered example.

Terracotta busts of women were often used as votive offerings across the Roman world. Worshippers left small figures in shrines, temples or within domestic spaces associated with household religion. Examples of this kind are uncommon in Britain, which makes the Magna discovery particularly significant.

The repeated appearance of the same female image at a frontier fort raises intriguing possibilities. It could point to focused devotion among the soldiers stationed there, their families, or traders living and working along Rome’s northern frontier. Whether the figure represents a goddess, a local deity, or a woman of high status remains uncertain, but the symbolism clearly mattered to someone.

The earlier head also has an interesting modern history. In the late nineteenth century, it was owned by Mary Ann Henderson, the last member of a family living at Carvoran Farm. She likely found it locally before selling the farm in 1885. The object remained in family hands for decades before eventually being donated to an antiquarian society.

While long gaps between discovery and museum acquisition often mean valuable archaeological context is lost, the survival of the piece has still proved invaluable. Without it, the significance of this newly discovered head might not have been recognised so quickly.

The newly unearthed head will soon go on display at the Roman Army Museum alongside other recent finds from the Magna project. These include leather shoes, a silver ring, bone hairpins, glass beads and a small figurine of Venus.

Together, these discoveries are helping to paint a richer picture of everyday life, belief and local craftsmanship along Rome’s northern frontier. Even a small fragment of clay, roughly shaped and imperfect, can open a window onto the people who once lived in the shadow of Hadrian’s Wall.