Hidden Roman Texts Found on Wax Tablets in Belgium’s Oldest City!

Fragments of wood excavated nearly a century ago in Tongeren, Belgium, are now transforming our understanding of daily life and administration in a northern Roman city. Once dismissed as debris, these modest remains have been revealed as the frames of Roman wax tablets, preserving faint but readable traces of texts thought to be lost forever.

The breakthrough comes from a collaborative study by Markus Scholz of Goethe University Frankfurt and Jürgen Blänsdorf of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. By re-examining wooden fragments recovered during excavations in the 1930s, the researchers uncovered previously unreadable inscriptions that shed new light on law, education, and civic administration on the Roman frontier.

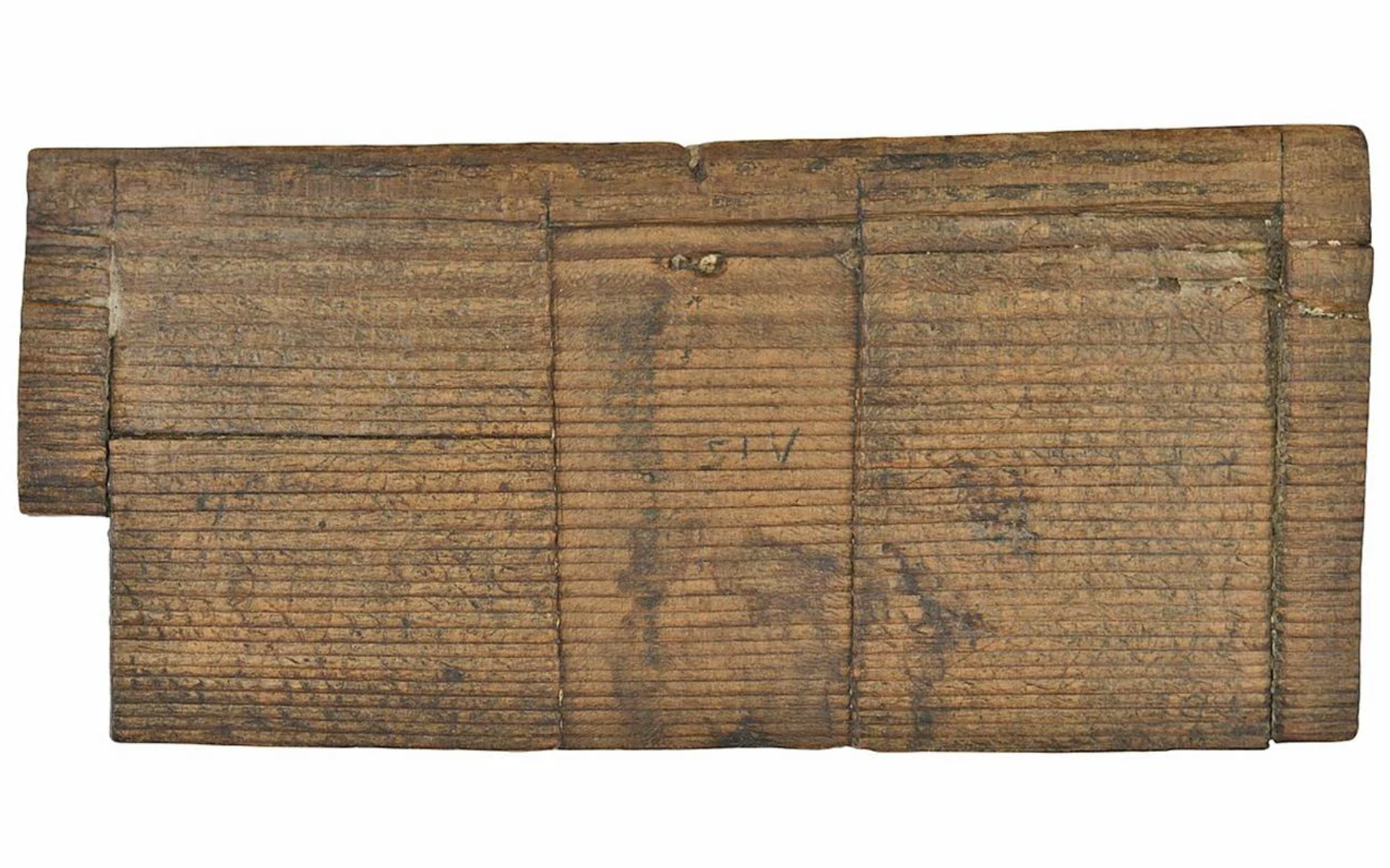

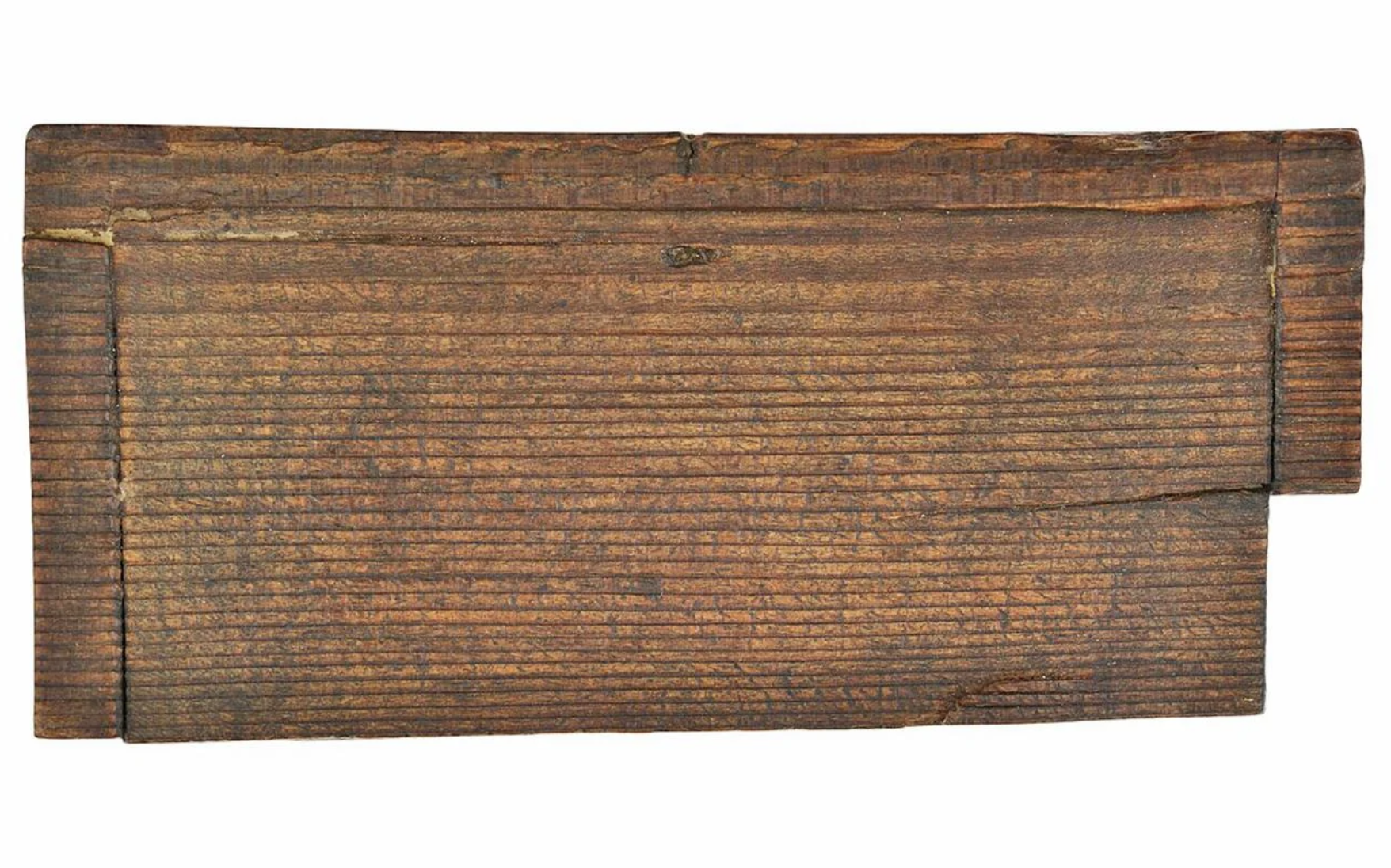

Tongeren, known in antiquity as Atuatuca Tungrorum, is widely regarded as Belgium’s oldest city. Archaeological investigations there have been ongoing since the early twentieth century and have produced a wealth of Roman material. Among these finds were small wooden pieces originally thought to be parts of boards or containers. It was only later that scholars recognised them as belonging to wax tablets, a common Roman writing tool used for contracts, official paperwork, and teaching.

Wax tablets consisted of wooden frames holding a thin layer of wax. Text was written by pressing a stylus into the wax, and in many cases that pressure left subtle impressions in the wood beneath. While the wax itself disappeared long ago, these underlying marks survived. For decades, however, they were assumed to be unreadable and were largely ignored.

That changed in 2020, when Else Hartoch of the Gallo-Roman Museum in Tongeren took a fresh look at the fragments and suggested that further analysis might be worthwhile. Scholz and Blänsdorf began systematic work the following year, though the task proved far from straightforward. The wood had completely dried out, and natural grain patterns, cracks, and surface damage often obscured intentional markings. Many tablets had also been reused, meaning traces of different texts overlapped.

Advanced imaging techniques, including reflectance transformation imaging, helped to highlight subtle surface details, but repeated close inspection of the original fragments remained essential.

In total, the team examined eighty-five fragments from two distinct archaeological contexts. One group came from a well close to the forum and public buildings. The damage suggests these tablets were deliberately broken before being discarded, likely to prevent sensitive information from being read later. Texts from this group include contracts and administrative records. Because scribes tended to press hard when drafting legal documents, these tablets were more likely to preserve deep impressions in the wood.

The second group was recovered from a muddy pit filled with refuse used for drainage. These fragments showed a much wider range of content. Among them were administrative copies, writing exercises produced by learners, and even a draft inscription intended for a statue of the future emperor Caracalla, dating to AD 207. This draft is particularly valuable, as it offers a rare glimpse into the preparatory stages of public monuments.

Only around half of the fragments preserve legible traces, but even this limited material significantly expands what we know about Roman provincial life. The texts mention a decemvir, a senior magistrate, and lictors, attendants of high-ranking officials, roles that are rarely documented in northern provinces. Personal names recorded on the tablets reveal a diverse population, combining Roman, Celtic, and Germanic backgrounds. Several individuals appear to have been former soldiers who settled locally after their service, including veterans of the Rhine fleet.

This study highlights the importance of careful, patient work on even the most unassuming archaeological materials. These small wooden fragments preserve valuable details about legal practices, education, and social organisation in a Roman frontier city, adding fresh depth to our understanding of provincial life during the second and third centuries AD.