How Pompeii Revealed the Secret of Roman Self-Healing Concrete!

A remarkable discovery in Pompeii is transforming our understanding of how Roman builders created some of the most durable concrete the world has ever known. Preserved by the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, an unfinished construction site has provided rare, time-capsule evidence of Roman building methods, and revealed how their concrete was able to repair itself.

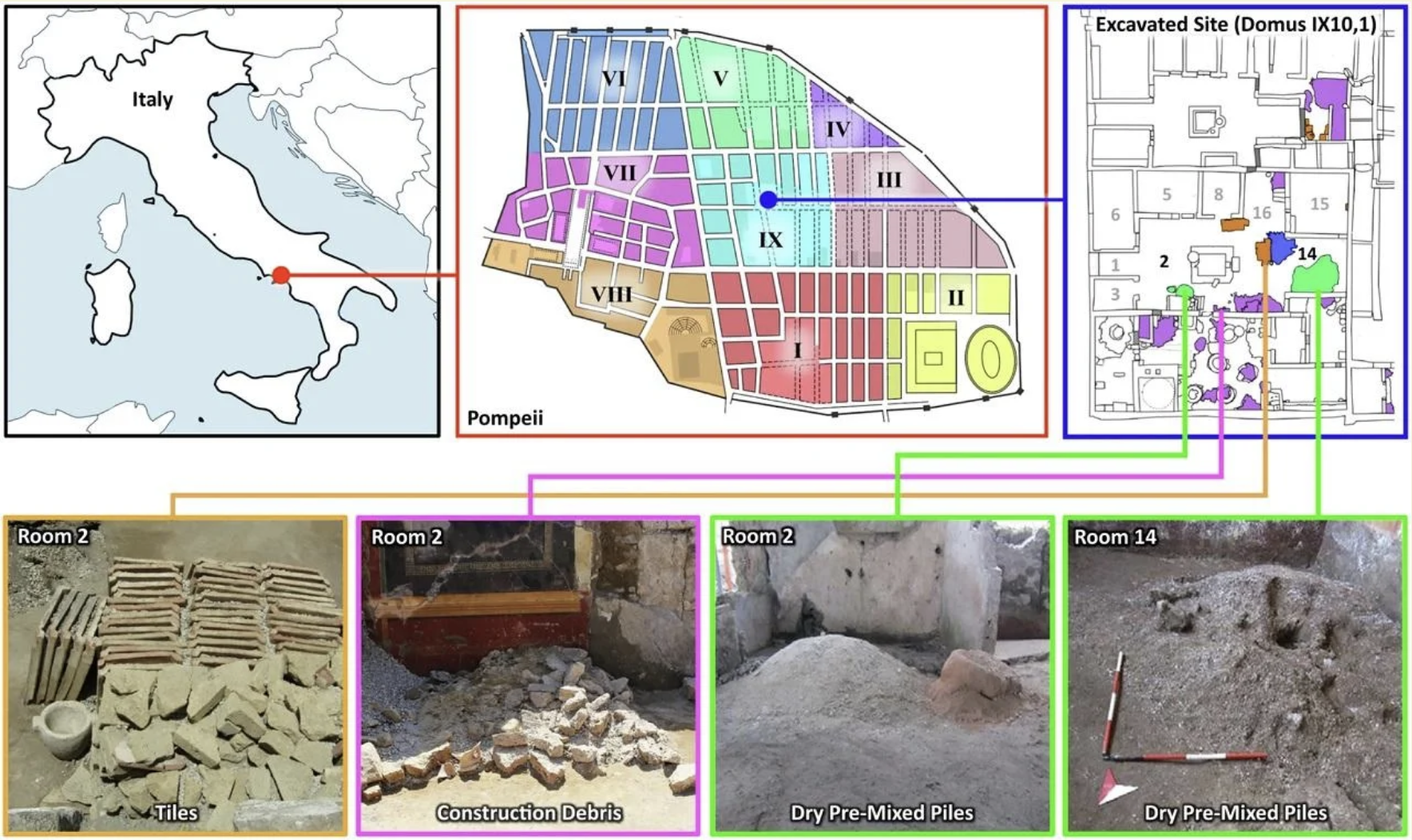

The site, located in Pompeii’s Regio IX, captures a building project that was still in progress when disaster struck. Tools, stacks of tiles ready for reuse, amphorae used to carry materials, and neatly arranged piles of dry construction ingredients were all left exactly where Roman workers had abandoned them. This unusual snapshot has allowed researchers to reconstruct, step by step, how Roman concrete was made, mixed, and applied.

A research team led by scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analysed the materials using chemical and microscopic techniques. Their findings, published in Nature Communications, show that Roman builders used a method now known as “hot mixing”. Instead of adding water at the start, they first combined quicklime with volcanic ash, or pozzolana, in a dry state. When water was later introduced, it triggered a powerful chemical reaction that generated intense heat.

Photo Credit: E. Vaserman et al., Nature Communications (2025); CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

This process created a distinctive internal structure within the concrete, leaving behind tiny fragments of partially reacted lime, known as lime clasts. Far from being flaws, these clasts turned out to be crucial to the concrete’s longevity.

When cracks form and water seeps into the material, the lime clasts react and release calcium. This calcium then crystallises within the cracks, effectively sealing them over time. The researchers found clear evidence of this process in the form of mineral growths such as calcite and aragonite lining old fractures. While similar self-healing behaviour had been observed before, notably in the tomb of Caecilia Metella near Rome, the Pompeii site provides the clearest proof yet that this capability was built into the concrete from the very beginning.

The findings also shed new light on ancient Roman writings. Vitruvius famously described combining lime and pozzolana, but made no reference to hot mixing, which led historians to assume a gentler process. However, Pliny the Elder wrote about the extreme heat produced when quicklime comes into contact with water, a detail that now makes much more sense in light of the Pompeii evidence. Together, the texts and the archaeology suggest Roman builders actively experimented with different techniques, adjusting their methods to suit local materials, environmental conditions, and structural demands.

That said, this advanced approach was not universal. Ancient writers themselves complained about poorly made mortar causing buildings to fail, even in Rome. Pompeii represents skilled craftsmanship rather than a standard practice across the empire. Researchers are still investigating how widespread hot mixing was, whether it evolved over time, and whether it may have been influenced by the region’s frequent earthquakes.

Even so, this frozen moment in Pompeii has provided invaluable insight into Roman engineering and may yet inspire modern approaches to creating longer-lasting, more sustainable concrete today.